Green reform of EU’s agricultural policy

Therefore, there is already a need for EU governments to start working on the next CAP after 2027. Beyond 2027, the focus should be on an overall systemic transformation, that at the same time reduces agricultural emissions, protects and improves biodiversity and maintains efficient food production .

In the future, there will be more people on earth, and if no one should go to bed hungry, and we also want to improve biodiversity and achieve climate targets, agricultural support must be transformed and targeted so that it promotes agricultural products with a low climate footprint with less land requirement’

The four guiding principles for any adjustments in the coming years, and especially for the next reform of the common European agricultural policy after 2027, are set out below:

CONCITO's recommendations

- The CAP should support an agricultural production system that supplies sufficient food as land efficient as possible - taken into account other environmental conditions

- Future CAPs must be designed to ensure climate impact in the agricultural and land use sector

- The CAP subsidies must favor production of low-emission food and agricultural products

- The CAP should contribute to the improvement of biodiversity in the Member States and the EU as a whole

The previous CAP did not deliver on climate and biodiversity

It is clear from several evaluations that the previous CAP (2014-2020) did not meet either the climate or biodiversity targets. Greenhouse gas emissions have not changed significantly since 2010, and the biodiversity of agricultural areas has not improved. This despite the fact that 66 billion euros of the CAP budget was earmarked for biodiversity and 100 billion euros for climate in the previous CAP period.

Greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector in the EU have fallen by approx. 21 per cent from 1990-2020, but there have been no significant changes during the most recent CAP period, as territorial emissions have been fairly stable since 2010 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Greenhouse gas emissions from the EU's agricultural sector. Source: EEA greenhouse gases - data viewer

At the same time yields of the main cereals, including wheat, maize and barley, have been just slightly increasing in the 2014-2022 CAP period, while yields of meat (poultry, pork, and beef) have been increasing an average of 5 % in the same period. This means that emissions per unit have been decreasing, and efficiency has increased. This shows a positive track, however, it is not enough to reduce the agricultural emissions in the EU, as production has increased at the same time.

From January, the new CAP (2023-2027) came into force after several years of negotiations and delays. The new CAP sets targets that aim to contribute to climate action and improving biodiversity on the fields. However, the EU agricultural policy continues at the same time to support the overall traditional production systems, which fall short in terms of actually prioritizing the production of food with a low climate footprint and low land use requirements.

The new CAP can provide a small reduction in EU GHG emissions from agriculture, as well as limited increase in regional biodiversity. This is mainly due to the new conditionality which requires 4 % of the agricultural land not be used for production. However, it requires more long-term measures to fully exploit the potential, and the war in Ukraine has led all EU counties, except Denmark to, postponing the introduction of several new green measures from the CAP, in order to avoid a possible decline in production and maintenance of food security.

In addition, the new CAP still contains production support, and continues to enable large financial support for some of the most climate-damaging forms of production, including especially the cattle sector. At the same time, in the EU there is a misalignment of political prioritization between the need to reduce emissions from the agricultural sector, the ambition to improve biodiversity, and the strong political incentives to produce biomass for bioenergy, e.g. via energy crops and wood. A high use of bioenergy results in an increased need for land for agricultural production and more emissions from agriculture and land use both in- and outside the EU.

Based on the EU countries' current national policies and measures, greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are only expected to decrease by approx. 1.5 per cent between 2020 and 2040. This underlines the need for new and stronger EU policies partly to reduce agricultural emissions and partly to increase carbon uptake in the land and forest sector.

The development of the next CAP post-2027 will probably start as early as 2024 and the current Commission will most like publish a communication of the post-2027 CAP with the next year. In addition, it cannot be ruled out that the food situation in the EU and the rest of the world will necessitate adjustments to the current agricultural policy before 2027, which e.g. the food crisis has already brought about.

Below, CONCITO presents its proposal for four guiding principles for possible adjustments in the coming years, as well as a basis for the next CAP reform post-27:

1. The CAP should support an agricultural production system that supplies sufficient food as land efficient as possible - taken into account other environmental conditions

Many estimate that the demand for agricultural products for food, energy, feed and fiber is significantly increasing globally. It depends on many different variables, such as population growth, a growing middle class, future global food diets and incentives for utilizing bioenergy and biomaterials. The World Resources Institute estimates that the agricultural area will increase by approx. 600 million ha. in 2050 to be able to meet the future demand for agricultural products, and that is even if the yields from agriculture continue to grow at the same annual growth that has defined the last decades.

At the same time, the global objectives on climate and biodiversity require that the need for agricultural products does not lead to further conversion of natural areas for agricultural production. Therefore, the Common European Agricultural Policy should support land-efficient production systems, which will reduce the global pressure to convert nature into agriculture – an approach also called 'sustainable intensification' by the IPCC.

Continued focus on yield improvements and increased productivity is crucial both in plant and livestock production to meet the increasing demand and at the same time preserve nature. This must be done in parallel with true efforts to reduce demand for the land- and carbon intensive agricultural products in wealthy countries, as well as taking into account the local environment and animal welfare standards to avoid negative side effects.

2. Future CAPs must be designed to ensure climate impact in the agricultural and land use sector

The previous CAP (2014-2020) had little impact on creating incentives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, which have not changed significantly since 2010 (approx. 1.5 per cent increase). This is due to both stable livestock emissions and increasing emissions from artificial fertilizers and livestock manure. Furthermore, the former CAP continued to support agriculture on drained peatlands, the cattle sector, and the funds for the restoration of organic soils were rarely used. In addition, support for afforestation was not increased in the previous CAP.

The new CAP (2023-2027) will to some extent contribute to reductions of greenhouse gases from agriculture based on the territorial principle, i.e. within EU’s borders, as the new reform will support a small extensification of the EU's total agricultural area. This is due to both the requirement of 4 per cent. non-productive areas and other incentives for conversion of agricultural land to more nature via eco-schemes and Pillar II funds. This will reduce the need for fertilizer, and in some cases lead to greater carbon storage. In Denmark alone, it is estimated in the agricultural agreement from 2021, that the new CAP reform will result in an annual reduction of approx. 1.5 million CO2e in 2030. However, this is not sufficient to reach the Danish target of 55-65 per cent. reduction in the land sector (agriculture and land use) in 2030 compared to the 1990 level, as this will require a reduction of 6.1-8.0 million tonnes of CO2e.

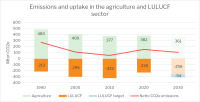

The EU has just adopted a common target of net intake of 310 million tonnes of CO2e in the land and forest sector (LULUCF) in 2030. The EU Commission also presented an ambition to achieve climate neutrality in the total land sector in 2035 (including emissions and removals in land, forest and agriculture), illustrated in the figure below. If agriculture were to contribute to achieving climate neutrality in the overall land sector, this would mean a reduction of approx. 20 percent of the emissions compared to the 2020 level to balance the net absorption in LULUCF of 310 million tonnes of CO2 storage. The LULUCF target obliges Member States to store a total of approx. 25% more CO2 in 2030 compared to the 2020 level. However, it was not possible to reach an agreement on this in the ‘Fít for 55’ negotiations.

Historical greenhouse gas emissions and uptake from the EU's agricultural sector (massive filling) and projection to 2030 (patterned filling). Data for the years 1990-2020 are based on reported data from the EEA greenhouse gases - data viewer, whereas 2030 is based on projections presented in impact analyzes in ‘Fit for 55’ 'mix' scenario.

The emissions from the agricultural sector should be closely monitored, e.g. via already existing outlook reports from the EU Commission, and measures to ensure reductions should include regulation of CAP support. However, this regulation should not prevent incentives to continue to increase efficiency in production.

3. The CAP subsidies must favor production of low-emission food and agricultural products

In the past two decades, the production of meat has increased by 9 per cent on average in the EU, while global demand for meat has increased by 15 per cent. over the past decade (UNEP, unpublished). Globally, the demand for meat is expected to increase between 50-144 per cent. towards 2050 (Ibid.).

For the most essential productions of meat, including pigs, poultry and cattle, there has been a significant increase in yields with an average of 5 per cent. from 2014-2020. Emissions from animal husbandry in the EU account for approx. 70 percent of agriculture's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2020, of which emissions from cattle make up approx. 60 per cent. At the same time animal husbandry receives significant direct and indirect financial support via CAP.

The financial support for protein production should generally be reprioritized so that proteins with a low climate footprint are favored, such as plant proteins for human consumption, alternative proteins and the animal productions with the lowest climate footprint and land use requirements such as poultry. CAP support should only be given to cattle and other animal productions with a large climate impact if it directly supports nature conservation that maintaining and improving biodiversity.

4. The CAP should contribute to the overall level of biodiversity in the Member States – not only focusing on on-farm biodiversity

In 2011, the EU adopted a biodiversity strategy for the period 2011-2020, in which there where commitments from the agricultural sector to improve biodiversity, which the former CAP (2014-2022) was supposed to help deliver. While there is limited measurement of the impact of agricultural policy on biodiversity, recent evaluations show that the CAP so far has failed to improve biodiversity in agriculture.

In 2020, the EU got a new biodiversity strategy, in which agriculture also plays a decisive role, as this sector must help create favorable conditions for nature. The conditionality in the current CAP regarding non-productive areas has a real, but limited, potential to improve biodiversity. However, these conditionalities have been postponed in most EU countries due to the war in Ukraine, and the increased focus on food safety. In addition, the potential for improving biodiversity will depend on the quality of the new eco-schemes and how great the demand is for the support for afforestation and nature restoration.

More specific and concrete mechanisms for protecting and improving biodiversity should be included in future CAP plans. In addition, it should support a general improvement of biodiversity in the member states, and not only target arable area, as the potential is generally higher outside the cultivated areas.

Information about CAP

The three most significant changes in the new CAP are:

1. The enhanced conditionalities for the direct income support

2. The flexibility to implement the EU's agricultural policy through national strategic plans

3. A new form of direct support for environmentally friendly agriculture via so-called eco-schemes

Brief history of environmental integration in the CAP

1962: birth of the CAP, focused on European market support and increasing supply of high quality, safe and affordable food

1980s: first voluntary agri-environment schemes were introduced

1992: MacSharry reform - decreased guaranteed payments connected to arable crops and livestock as well as compensation to farmers if they adhered to certain conditions

1999: Agenda 2000 started the integration of environmental measures into the CAP. Pillar II was established and increased support for rural areas and promoted environmental measures

2013: Climate action became one of the objectives of the CAP, green payments were rewarding farming practices